I recently read the following definitions:

Puzzle: Pivots around lack of information e.g. Watergate scandal, Osama bin Laden’s whereabouts. Can be solved with more information.

Mystery: All the information is available to everyone but the mystery can be resolved only when someone has the time, expertise and tools to analyze the information and spot the hidden red flags. e.g. Enron and Satyam failures, Great Financial Crisis of 2008.

– Malcom Gladwell

A mystery thrives on complexity. No amount of transparency or disclosure will help in cracking it.

Per Gladwell, “It’s like saying, ‘We’re doing some really sleazy stuff in footnote 42, and if you want to know more about it, ask us.’ And, gee, that’s the thing, nobody did.”

In the aftermath of the recent financial crisis where complex financial products blew up and resulted in huge losses to investors, experts and public alike are clamoring for greater transparency from financial institutions. By knowing more about all the risks involved in such products, they say, they’d be in a position to take more well-informed decisions and avoid such problems in the future.

This is a misguided stand. These people are treating financial products as a puzzle and attributing the crisis to lack of information. Which is not the case – these financial products were more like mysteries. A lot of information is available to us when we decide to buy them. It’s just that we don’t – or can’t – penetrate their fancy packaging to analyze the fineprint or spot the landmines that will inevitably blow up some day in the future.

If you want proof, just check how many people can decipher 2/28, ARM, CDO, CDO-squared, CDS, and other fancy financial products I’ve written about in the post “Is Catch-22 Coming True?” at the height of the crisis.

Let me now take an example from my personal experience to illustrate how financial products are akin to mysteries, not puzzles, and why no amount of additional information is likely to help the average investor.

A few years ago, I wanted to park some one-time surplus cash. I was on the search of a financial product that called for no more than one or two payments. The MNC bank where my salary account was held suggested a Unit Linked Investment Policy (ULIP) from a leading multinational insurance company. While buying this policy, I was assured that I could stop making premium payments after the second year. I was also told that returns from the policy were subject to market fluctuations. Since this was a standard disclaimer, I thought no more about it.

Cue to the present day: The Indian stock market has trebled since I bought this product but my portfolio value has barely crossed the principal.

When I asked the insurer why this was the case, I was told that, since I’d stopped paying premium after the second year, my policy had gone into a so-called “paid-up” mode.

When I asked the insurer why this was the case, I was told that, since I’d stopped paying premium after the second year, my policy had gone into a so-called “paid-up” mode.

When I told them that meant nothing to me, they explained that, as per the terms of the policy, when a policy goes into paid-up mode, the management fees for the entire tenure of the policy (20 years in this case) would be recovered immediately after the second year – which is what put a big dent to my portfolio value.

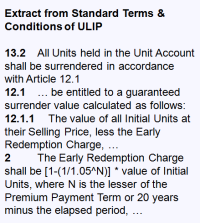

This came as a rude shock to me and I finally decided to open the Standard Terms & Conditions that had accompanied the policy documents a few years ago. After wading through ten pages of fineprint, I was able to locate a set of clauses (cf. exhibit on the right) that seemed to indicate that, while the insurer could deduct units proportionate to the management fees for the full policy term if the policy went into paid-up mode, they could do so only if the policyholder surrendered the policy and sought premature redemption.

Since I was still holding on to the policy, there was no question of the deduction applying in my case.

When I pointed out these clauses to the branch staff and call center representatives, they were clueless on how to interpret them despite the fact that they were present in their own agreement. They deflected me to some email address. Six months and two reminders later, I still don’t have a reply to my email.

To me, this experience illustrates the following points:

- The salespersons of the bank and insurer had not explained the possibility of such huge deductions to me and had hidden behind the general disclaimer that linked returns only to market fluctations. To that extent, they certainly engaged in mis-selling.

- In not responding to my recent emails seeking clarification, the insurer is guilty of poor customer service.

However, the basic structure of this product (i.e. ten pages of terms and conditions for a consumer product) and my decision (to buy it without reading the terms and conditions) make this a mystery, not a puzzle.

UPDATE DATED 9 MAY 2018:

Today, I read an article on Poynter, which provides some background on the nature of puzzle and mystery.

The global threat to free media: Four ways journalism gets BLOC’d

(In) his 1985 book “Amusing Ourselves to Death”, media thinker Neil Postman compared the politics of George Orwell and Aldous Huxley: “Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egotism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance.”

Quite clearly, Orwell’s style is akin to puzzle and Huxley’s style is akin to mystery.

UPDATE DATED 7 JULY 2021:

I finally found a good explanation for why the said bankers / insurers were clueless about the formula in the aforementioned contract.

Copy-pasting from today’s edition of Money Stuff newsletter by Matt Levine.

A major problem in finance is that a lot of lawyers became lawyers because they did not like math, while a lot of bankers and traders became bankers and traders because they did not like to read. So lots of financial contracts will consist of 10 or 50 or 200 pages of text, which a lawyer will cheerfully write (or sullenly copy and paste, fine) but which her client will not read, and buried within those pages there will be like three formulas, which the lawyer will write and which might be wrong. The lawyer, who fears math, will write the formula wrong, and her client, who knows math but fears words, will not read it, and so the wrong formula will be enshrined in the contract.

This is just the first paragraph of the section titled Inflation indexing in the newsletter. I strongly recommend the entire section. In keeping with Matt Levine’s trademark style, it’s not only enlightening but hilarious.

This provides the theoretical underpinning of what goes by “misselling” in public discourse.

UPDATE DATED 30 JUNE 2022:

12 years after my original post was published, nothing much has changed in the world of sales of financial investment products.

Copy-pasting from today’s edition of Money Stuff newsletter by Matt Levine.

UBS recognized and documented the possibility of significant risk in YES investments, it failed to share this data with advisors or clients. As a result, … some of UBS’s advisors did not understand the risks and were unable to form a reasonable belief that the advice they provided was in the best interest of their clients. When investors suffered losses, many of them, along with their financial advisors, expressed surprise and closed their YES accounts.

But, says the SEC, the advisers didn’t really know what they were selling: Beyond standard language along the lines of “[s]ignificant market moves either up or down may result in losses” and “[s]elling options involves a high degree of risk,” none of the written materials provided further explanation of the downside risk of YES. …It’s hard.

On the one hand, if you are a financial adviser, you want to give your clients good financial advice, which means understanding the nuances of the products you are selling them. On the other hand, if you are a financial adviser at a big brokerage, you want to give them a lot of financial advice, both because you will endear yourself to (some) clients by selling them lots of whizz-bang stuff that they can’t get anywhere else, and because you will endear yourself to your employer by selling stuff that makes a lot of money for your employer. And doing that tends to be easier if you don’t understand the nuances of the product. If your understanding of a product is limited to “this thing is called YES and it never goes down,” then you will be excited to sell it.

Pingback: Stocks Always Underperform Fixed Deposits « Talk of Many Things

29 pages Offer Document for Delisting Offer. Whoa!

Maybe it’s only me but I want less – not more – transparency from sellers of financial products. #Puzzle #Mystery #MalcomGladwell

Pingback: Why Nobody Went To Jail For Great Financial Crisis | GTM360 Blog