Most of us are familiar with Cost-plus and Value-based pricing, which are the two most commonly used methods for pricing products and services.

In cost-plus pricing, all input costs are totalled up and a markup is applied on top to arrive at the selling price. More the number of inputs, higher the cost and, ergo, higher the price. By nature, cost-plus pricing is bottom-up and fairly transparent / whitebox.

In value-based pricing, the selling price is set based on perceived value of pain solved or gain created (“value”), brand, competitor prices, and other factors that may or may not involve additional inputs. By nature, value-based pricing is top-down and quite opaque / blackbox.

Here are a few broadbrush observations about these two pricing methods:

- Unbranded products follow cost-plus pricing

- Branded products follow value-based pricing

- Regulated products tend to follow cost-plus pricing.

- In a free market, the manufacturer or service provider should be free to set prices. However, from time to time, the government could intervene with price controls where the prices may be set at cost or even below cost. For example, during the current coronavirus outbreak, there are price controls on masks, PPE kits, hospitalization, etc. Soon after the GFC in 2007-8, there was a spate of regulation around banking fees and charges in USA. Dodd-Frank-Durbin Act capped debit card fees at 24 cents per transaction for banks above $5B in assets. While enacting this law, the lawmakers specifically linked price to cost and noted that fees for debit card transactions should be “reasonable” in comparison to the cost of processing them. Other examples where prices are controlled basis costs are credit card APR caps (US CARD Act), overdraft charges on checking / current accounts (USA, UK) and insurance premiums (Germany, India)

- Value-based price is higher than cost-plus price

- For every increase in input cost by (say) 10%, cost-plus price will go up by the same 10% but value-based price will inevitably go up by around 30%

- Value-based price sometimes drives an increase in price two times even when the input cost has increased only once. Although this is not a very common tendency, I’m sure homebuyers in Mumbai and Pune would have encountered it sometime or the other. The average housing complex has smallish – er, “compact” – bedrooms and quotes (say) INR 20K / sqft for a 1200 sqft apartment. Then comes a premium housing complex where rooms are bigger. Builder uses spaciousness as key attribute of premium branding and quotes INR 30K / sqft for the 2000 sqft premium apartments. Assuming that the branding sticks, people pay 30K * 2000 for the premium apartment as against 20K * 1200 for the regular apartment. As you can see, a onetime increase in the same input, spaciousness, has fetched an increase in price twice: 30K against 20K and 2000 against 1200. (I’m suspecting a similar practice in stock markets. Highly profitable companies have, by definition, a higher EPS; and, in practice, they also enjoy a higher P/E ratio, than other companies in the same sector. Since Price = EPS * P/E, such companies get a two time kicker in price for a onetime improvement in the input, namely, profit.)

Sometimes, it would be obvious to suppliers whether to adopt cost-plus pricing or value-based pricing.

Other times, there could be a tussle between the two pricing methods. Let’s take three examples of this nature and examine how brands have tackled pricing.

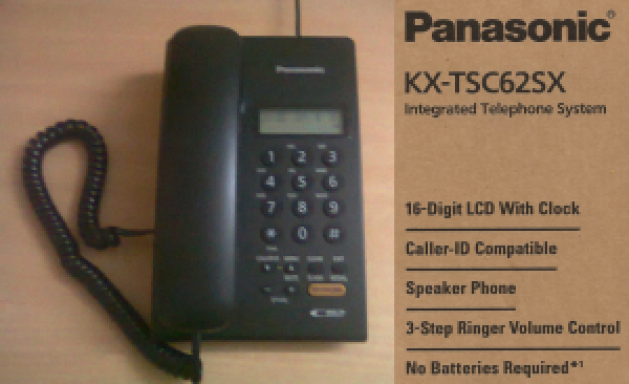

#1. PANASONIC

A few years ago, Panasonic launched a new model of desk phone called KX-TSC62SX. Readers would be aware that feature-rich handsets generally need batteries and a charger to charge the batteries, as a result of which they need to be plugged in to the mains at all times.

Unlike its older brethren, the KX-TSC62SX doesn’t use any batteries.

No batteries means no charger, therefore KX-TSC62SX has a lighter bill of material compared to previous models of Panasonic phones that require batteries and / or charger. According to cost-plus pricing, this model should be cheaper than other models.

At the same time, lack of batteries means no need to plug a KX-TSC62SX to the mains. Which means KX-TSC62SX doesn’t require a wire to be carted around and does not have to be tethered to a power socket. As a result, it alleviates a major pain area of conventional phones. According to value-based pricing, the KX-TSC62SX model should be costlier than other models.

Ergo there’s a tussle between the two pricing models. Since Panasonic does not have two variants of the same model with and without batteries, this tussle is implicit and can be sidestepped.

#2. ONLINE EDUCATION

Colleges are shut during the current Covid-19 lockdown.

Before Lockdown: Students attended the college in person. Teaching happened face-to-face.

After Lockdown: Students can’t visit their college. Teaching has moved online. Colleges are using Blackboard, Microsoft Teams, Zoom and other online collaboration platforms to conduct virtual classes.

Learning Experience (LX) has diminished. Going by value-based pricing, a college should lower its tuition fees.

On the other hand, the college needs to digitize study material and install high-speed Internet pipes. These are extra inputs. Going by cost-plus pricing, college should increase its tuition fees.

Fees have neither gone up or down.

There’s a stalemate between cost-plus pricing and value-based pricing.

That said, the situation is fluid. Ivy League university students in the US have started a petition for lowering fees. Universities are pushing back saying that not only have their costs increased but also that they were not recovering their costs from tuition before (and had to dip into their endowment funds to cover the full cost of education all this while). Only time will tell what will happen to the fees.

#3. WADESHWAR

Take the following two items in the menu of this iconic restaurant in Pune, India.

- Tea

- Tea (without sugar)

The first item has sugar whereas the second item does not. In other words, the first item has more inputs than the second item. Therefore, according to cost-plus pricing, the first item should be costlier than the second item.

But sugar is supposed to be bad for health. So the sugarless second item has a greater perceived value than the first item. Therefore, according to value-based pricing, the second item should be costlier than the first item.

Wadeshwar has broken the tussle between the two pricing methods by opting for value-based pricing, as you can see from its menu:

Tea: INR 33.00

Tea (without sugar): INR 38.00

Nice example of "value-based pricing" from @wadeshwar – under "cost-plus pricing", "Tea with Sugar" would have a higher price than "Tea (without sugar)". https://t.co/nG6UjOkDkY pic.twitter.com/7PmEpT02nC

— GTM360 (@GTM360) January 19, 2018

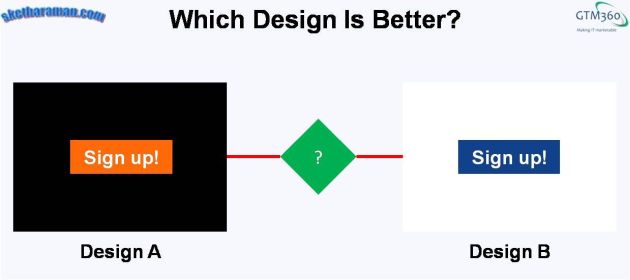

There’s a third and comparatively less-understood pricing method: What The Traffic Can Bear.

"What The Traffic Can Bear Pricing". Everyone understands "cost plus" pricing. Many understand "value based" pricing. But very few people (in my circle) understand that some brands can get away with exorbitant prices just because their target audience doesn't feel the pinch.

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) May 11, 2020

In this method, prices are way above cost as also the number dictated by value-based pricing.

In cost-based pricing, prices are X% more than input costs.

In value-based pricing, prices are X% more than competing products perceived as inferior.

Under What The Traffic Can Bear pricing, prices are N times more than perceived competing products. Perceived because only a bystander would think of them as competing products basis job to be done. The actual buyer wouldn’t even include them in his Initial Consideration Set. This pricing method is typically used for luxury goods having status symbol / snob appeal. By nature, it’s totally top-down and completely opaque / blackbox. Brands are able to get away with exorbitant prices just because their target audience doesn’t feel the pinch e.g. $5,000 Prada bags, $50,000 Patek Philippe watches, £25 Full English Breakfast in a London five star hotel.

The input cost of the last item is less than 50 pence. You can get the product in a regular streetside eatery for around £5. But it will cost £25 in a London five star hotel.

H/T to Hotel Babylon, a book by Imogen Edwards-Jones and Anonymous about the luxury hotel industry in London, for this example.

I recently came across a rather weird case of pricing.

Clinic Plus Shampoo:

- 650 ml bottle: INR 325

- 6 ml sachet: INR 1

H/T to our customer Anshuman Shrivastava, Director Toptier Energy Services and ex-Banker, for this example.

For the uninitiated, Clinic Plus is a popular shampoo brand that has been sold in the bottle form for a long time. The sachet is a more recent addition.

The Unit Price of the shampoo in bottle works out to INR 0.50 per ml (being INR 325 / 650 ml). Going by that figure, the price of the sachet should be INR 3 (being INR 0.50 per ml * 6 ml).

But the sachet is priced at just INR 1 i.e. three times lower.

What gives?

I’m guessing that the brand has kept a very low price point for the sachet in order to penetrate the “bottom of pyramid” market whose affordability is lower than that of the bottle-buying affluent consumers.

If so, this should be called What The Traffic Can’t Bear pricing method!

PS: I have borrowed the Panasonic and English Breakfast examples from a previous post.

UPDATE DATED 8 JANUARY 2023:

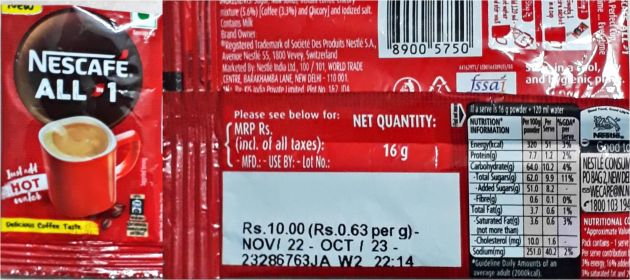

Nescafe Sunrise instant coffee is another product that seems to follow the What The Traffic Can’t Bear pricing method i.e. smaller-size sachet has a lower price / gram than larger-size bag:

- 2.2gm sachet * 156 nos. ~ 343gm ~ ?300 + 120 Shipping = ?420 ~ ?1.22/gm

- 50gm bag ~ ?95 ~ ?1.9/gm

- 200gm bag ~ ?350 ~ ?1.75/gm

- 500gm bag ~ ?830 ~ ?1.66/gm.

The cheapest of them all is NESCAFE ALL-IN-1 sachet:

16gm sachet ~ ?10 ~ ?0.63 /gm.

Since it includes milk and sugar, you just need to add hot water – and your coffee is ready!