A couple of years ago, virtually every driver of my Uber and Ola taxi rides used to praise the two cab aggregators to high heavens for paying them huge incentives. Many of them would ask me how these startups could afford to shell out that kind of money when they were collecting less than half of that amount in fares.

I used to tell them that they got truckloads of cash from VCs and explain how the venture capital model was driven more by bookings than revenues or profits.

Cue to the present day. There’s still a lot of mystery shrouding VC funding.

Cue to the present day. There’s still a lot of mystery shrouding VC funding.

I regularly come across hordes of people during events and on social media dunking on VCs for ruining the market by promoting discounts and cash burn. Some of the haters have even gone so far as to suggest that the government should ban VCs.

In this post, I’ll share my thoughts on why this belief is totally wrong and share my understanding of how the VC investment model works.

Much of the angst about VCs arises because people wrongly apply the yardstick of a traditional business to VC investments.

Let’s take a traditional business like cement. Promoters and shareholders make a large upfront investment to set up a factory, develop a distribution network and employ staff. While a plant is under construction – which can easily take 3-5 years – there’s no revenue. After production commences, sales begin, hopefully profits and dividends follow, share price goes up and shareholders start seeing a return on their investment. For the first five years or so, investors get no return on their investments. Therefore, there’s a lot of time burn in a traditional business.

On the contrary, there’s very little time burn in the VC funding model. The way it works, revenues start from Day One in the case of cab aggregation, ecommerce and many other VC-funded categories.

Once they achieve product market fit, startups use the funds raised from VCs to achieve explosive – aka “hockey stick” – growth in Pageviews, App Installs and Gross Merchandise Value.

If the market is favorable, growth on these so-called “vanity metrics” translates into a manifold jump in the valuation of startups. Angels investing in startups at the early stage can sell their shares to VCs, PEs and other late stage investors for a tidy profit even if the startup hasn’t started making profits.

VC in Bangalore looking for "Startups with great vanity metrics and excellent knowledge of buzzwords!" via a friend (@renjipanicker) pic.twitter.com/RAe58yRsIS

— Tarak Parekh (@tparekh) May 11, 2017

Many people find it unreasonable that valuations keep raising when a startup’s losses are mounting.

They shouldn’t. In what’s one of the cardinal principles of investing, valuation is what the buyer and seller mutually agree upon – there’s nothing reasonable or unreasonable about it.

Not that there aren’t theories about estimating valuation or practical applications of the theoretical models.

Not that there aren’t theories about estimating valuation or practical applications of the theoretical models.

In his blog post titled Valuation For Startups?—?9 Methods Explained, the author Stéphane Nasser explains several methods of arriving at a startup’s valuation.

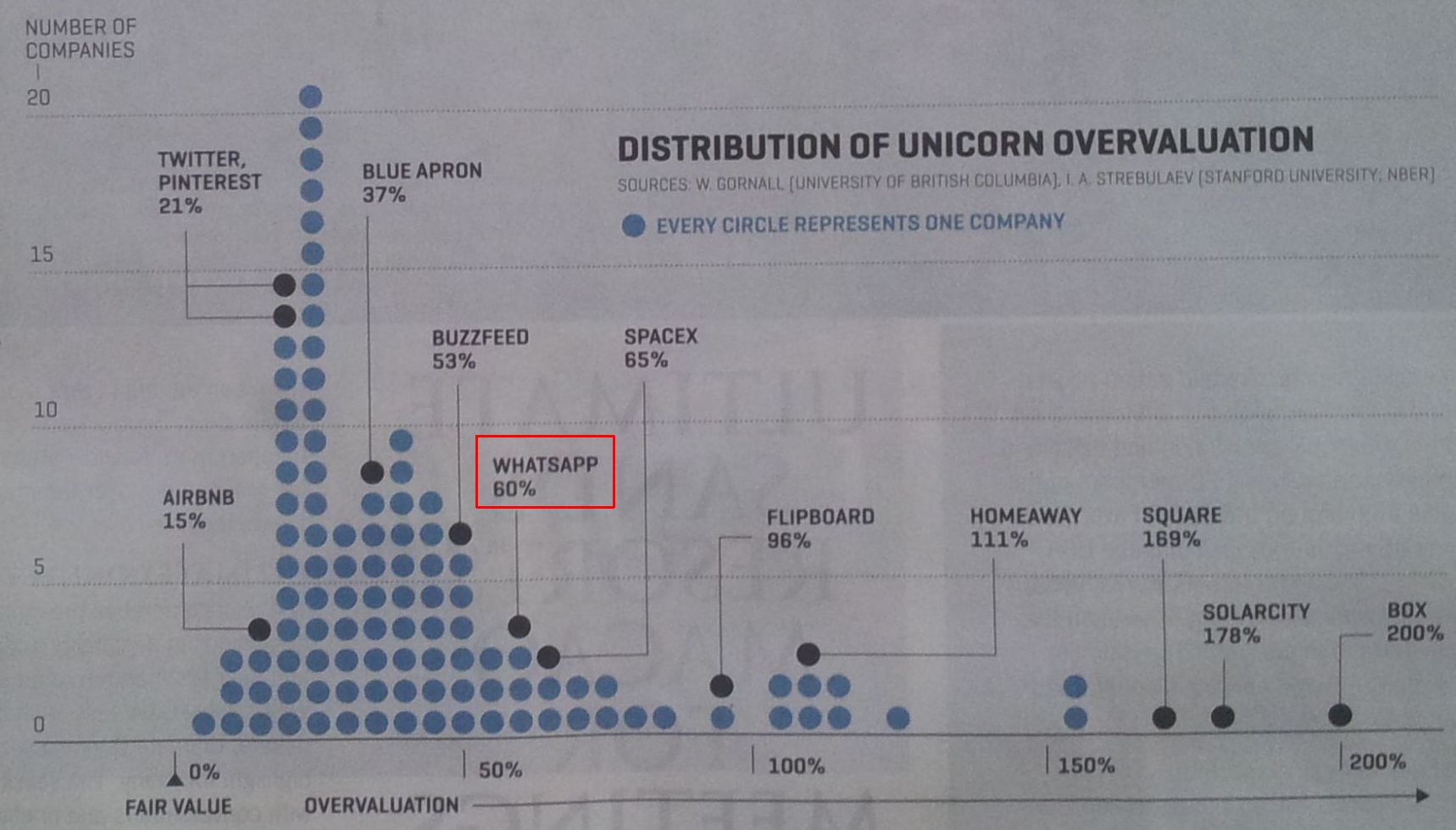

According to a study cited by FORTUNE in Tech Unicorn Valuations Are In Trouble, “half the unicorns were worth less than $1 billion, and more than a dozen were overvalued by 100%”.

While these models and studies sound logical on the surface, they tend to break down when you probe them deeply.

Models use thumb rules like “P/E ratio of 30 is a bargain for a consumer internet startup”, “P/E ratio of 20 is too high for an IT services company”, and so on. There’s nothing intrinsically scientific about these rules of thumb.

By concluding that WhatsApp was overvalued by 60%, the aforementioned study cited by FORTUNE implies that the right value of WhatsApp is 40% of the $19B paid by Facebook for it.

Well, if a valuation of $7.6B (40% of $19B) makes sense for a company with sales of $36M, so should the actual valuation of $19B.

Then, there are other scientific-sounding articles like Behind the global tech investing tsunami that justify exploding valuations for VC-funded startups.

But these models have limited use. They can be used to have objective conversations around valuation before a deal is struck. However, after a deal happens, nobody cares about objectivity. All that matters is the price at which the buyer and seller struck the deal. What others say is immaterial.

It’s not only me. As Stéphane Nasser concludes his aforementioned article, valuation models “are just the theoretical introduction to a more significant game of supply and demand.” In plain English, you decide on a valuation and then use a scientific model to rationalize the figure.

And, this is not just true of VC-funded startups. As Joseph Heller wrote in his bestseller Picture This many decades ago:

‘Aristotle Contemplating The Bust of Homer’ is the most valuable painting because it’s the most costly painting; it’s the most costly painting because it’s the most valuable painting.

He was referring to the Rembrandt masterpiece that was the first painting in the world to sell for more than a million dollars.

Bottomline is, as long as somebody is willing to buy shares of a startup at a certain valuation, it’s immaterial what third parties think about the valuation.

The success of the VC funding model lies in its ability to find such “somebodies” at scale and deliver alpha returns to them.

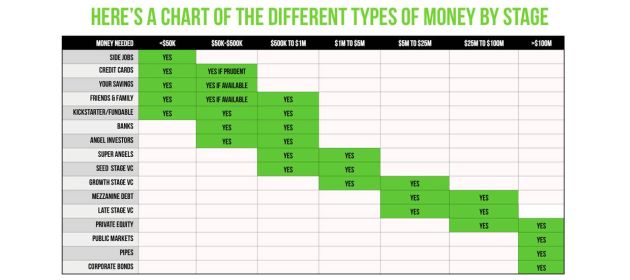

Early stage investors (“Angels”), who get into a startup early, make money by selling their stake to late stage investors (“VCs”). Late stage investors, who enter when the startup has started making revenues (but not profits), make money by selling their stake to later stage investors (“PEs”). Rinse and repeat until the last stage where private equity investors, who get into the startup once it makes significant revenues (but not necessarily profits), sell their stake to the man on the street via IPOs.

To be clear, “returns” do not come from dividends distributed by the startup but via capital gains accruing from the increase in the value of the investor’s stake in the startup from one round of funding to another.

While there’s cash burn, shareholders make money right from the inception of the startup. So, there’s no time burn in the VC funding model.

In the world, there are some people who are time rich and money poor and there are others who are money rich and time poor. Shareholders in traditional businesses are in the first category, so they prefer time burn to cash burn. VCs are in the second category, so they prefer cash burn to time burn.

Each to his own way. There’s no reason for the government to ban VCs for belonging to the second cohort.

Metrics of a conventional business are relevant in the VC model. But they apply to VCs, not their portfolio companies. That’s what I meant by the “VC is the Business” part of this post’s title.

VCs have a great track record on those metrics. That will be subject of a follow on post. Watch this space.