When consumers are asked to pay for some product or service, they think twice about whether to consume it.

There’s a cognitive overhead in all decisions but the one involved in micropayments is acute because it’s more mentally taxing to decide whether or not to spend, say, $0.10 to read an article than the $0.10 itself. Ergo, as Byrne Hobart notes in The Diff Capital Gains newsletter, consumers’ subconscious veers towards the all-you-can-eat subscriptions, which spare them the cognitive overhead of the buy-or-not-buy decision. That also perhaps explains Why Publishers Don’t Sell Individual Articles even though micropayments have been around for a decade or longer.

There’s a similar cognitive overhead in B2B technology procurement.

Back in the day, when companies learned that their servers and storage had an average utilization of only 30-40%, their CIOs and CFOs were immediately attracted to the usage-based pricing paradigm of public cloud infrastructure like AWS and Azure. For similar reasons, they moved from onprem COTS enterprise applications to SAAS software. However, when they’re asked to pay $100/month to add another user for the SAAS software, CIOs wonder if an existing user can’t handle the extra load and CFOs question if it’s necesary to buy an additional user subscription.

In addition, cloud creates the chore / anxiety / terror (choose one depending on company culture) of IT having to go to finance every month to get vendor payments released on time. God save the CIO if, in a given month, the cloud service provider slaps her with overage charges and the bill doubles or triples (which happens more often than you might think, see example here).

All of these tasks create massive cognitive overhead for IT.

To sidestep it, many CIOs sign up for three year contracts and pay subscription fees for a year or more upfront. I’m not sure how many CFOs have realized that this defeats the “pay-per-use” and “cancel anytime” raison d’être of cloud computing.

Coming to accounting, even if a customer signs up for three years and pays the entire subscription fees upfront, the cloud service provider / SAAS vendor cannot bill the total contract value (TCV) at one shot. This is because GAAP revenue recognition norms allow billing only in proportion to value rendered. Since the software is used continously through the contract period – and not lumpsum at the point the contract is signed – vendors can bill and recognize revenue only on a monthly or max quarterly basis. (Not accounting advice.)

Due to a similar rule regarding cost recognition on the buyer’s side, the aforementioned customer can’t book the cost of 36 months subscription fees at once but only on a month-by-month basis. This explains how a small cost can trigger a big cash outflow. (Not accounting advice.)

It could also explain the low training costs of DeepSeek.

Chinese quant hedge fund Zhejiang High-Flyer Capital Management (“High Flyer” from here on) recently launched an Artificial Intelligence Large Language Model called DeepSeek.

While most people may have heard about High Flyer and DeepSeek only after the launch, I’d read about it in the Money Stuff column by Matt Levine last June.

DeepSeek sent shockwaves throughout the world as soon as it open-sourced R1. On the very first day of trading after the launch, stocks of semiconductor and electric utilities crashed by a trillion dollars, with $NVDA alone suffering a $600 billion loss of market cap.

The huge impact caused by DeepSeek is attributed to three reasons:

- R1 matched the performance of the most powerful reasoning model in the world, namely, OpenAI o1.

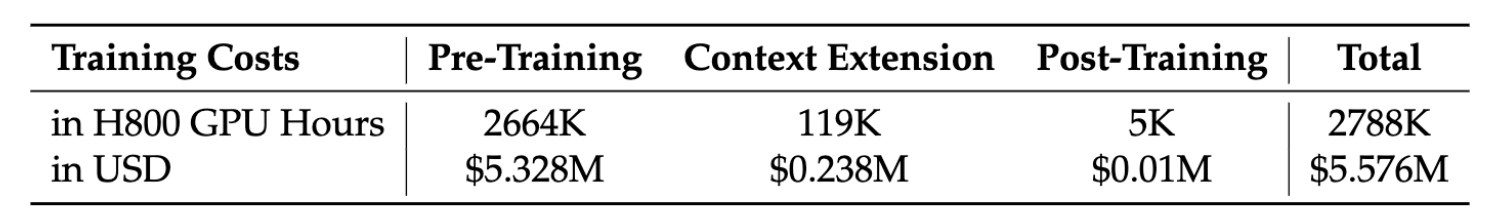

- Its training cost was only $6 million (as against the hundreds of millions spent by OpenAI, Anthropic and other western AI firms).

- It was open-sourced.

While the performance of R1 is verifiable by third parties, there’s tons of skepticism over DeepSeek’s claim of spending only $6M on training the LLM. If that figure is materially wrong, then giving it away for free via open source license may attract laws against predatory pricing. (Not legal advice.)

David Sacks, the new AI Czar of USA, asserted that that DeepSeek spent over a billion dollars to buy an NVIDIA GPU cluster.

@DavidSacks: New report by leading semiconductor analyst Dylan Patel shows that DeepSeek spent over $1 billion on its compute cluster. The widely reported $6M number is highly misleading, as it excludes capex and R&D, and at best describes the cost of the final training run only.

Some others have put the CAPEX at $2 billion.

Notwithstanding these figures, it’s quite possible that DeepSeek booked only the OPEX cost for the actual hours of training DeepSeek, which would obviously be a tiny fraction of the $1-2B CAPEX figure.

I was sold on this possibility after reading Ben Thompson / Stratechery‘s take on the subject:

DeepSeek claimed the model training took 2,788 thousand H800 GPU hours, which, at a cost of $2/GPU hour, comes out to a mere $5.576 million.

The OPEX could have been even lower than $5.576M if DeepSeek had used cheaper AI cloud providers – I’ve seen figures as low as 1.5/GPU/hour. If High Flyer owned the AI cloud and rented it to DeepSeek, the cost per GPU hour could have been even lower than $1.5/GPU/hour. If CCP did, anything is possible – this would not be the first time China has subsidized its products and services.

With due respect to the engineering innovation involved in R1’s high performance, the CAPEX-OPEX financial jugglery could explain its low training costs and its owner’s decision to open source it.

Switching between CAPEX and OPEX is similar to the Sale and Lease Back model used in the commercial real estate industry. Under SLB, a company sells a property it owns (e.g. office building, warehouse, or retail space) to an investor or real estate firm, leases back the property from the new owner under a long-term lease agreement, and continues to use the property while paying monthly or periodic lease payments. My first exposure to Sale and Lease Back was the headquarters building of HSBC in Canary Wharf in London. 15 years later, the first of SLB deals has started in India e.g. WNS in Viman Nagar in Pune. Click here to find out the benefits of SLB to both the original owner and the new owner.

Going by the number of conspiracy theories that High Flyer may have shorted Nvidia, Broadcom, other semi and electric utility stocks and pocketed a fortune, it can’t be ruled out that DeepSeek created a clever spin of projecting a high CAPEX cost as a low OPEX cost to create the trillion dollar market meltown.

What are the chances that @deepseek_ai’s hedge fund affiliate made a fortune yesterday with short-dated puts on @nvidia, power companies, etc.? A fortune could have been made.

— Bill Ackman (@BillAckman) January 28, 2025

We may never know what High Flyer did but Reuters reported that some others did short the Nvidia stock and rake in over $6 billion in profits after DeepSeek panic.