There’s a lot of buzz around cybercrime. Not a week goes by when we don’t hear of someone or the other losing money to scammers and fraudsters via UPI and other A2A RTPs.

Let’s consider the following ubiquituous cybercrime described in Why Is It So Hard To Catch Cybercriminals?.

Joe uses UPI to buy something from Jane, and does not get what he ordered.

While I’ve taken UPI as an example, this post is equally relevant for other types of A2A RTPs like FPS (UK) and Zelle (USA).

(For the uninitiated, A2A RTP stands for Account-to-Account Real Time Payment, where money goes from sender’s bank account to receiver’s bank account in near realtime.)

We concluded Fraud v Scam: Who Is Liable For Cybercrime on the note that the payor will be forced to take the fall for a cybercrime carried out with an A2A RTP. We also mentioned that banks will typically own cybercrimes conducted via credit card.

Which begs the following question:

Why can’t UPI / A2A RTP provide the same degree of scam / fraud protection as Credit Card?

It can’t because a Maruti 800 can’t be a BMW.

In this post, we will trace the roots of credit card and A2A payments and show why scam / fraud protection is a feature in credit card but a bug in A2A RTP.

In fact, the absence of scam / fraud protection is a USP of A2A RTPs since they were introduced in response to pushback from merchants over a diametrically opposite feature in credit card payments, which is variously called Repudiation, Revocability or Chargeback.

Let’s get into it.

When you use UPI, you use your money. UPI is a right.

When you use credit card, you use your bank’s money. Credit card is a privilege.

When somebody commits a cybercrime via UPI, they’re stealing your money. You’re on your own.

When somebody commits a cybercrime via credit card, they’re stealing your bank’s money. They invite the wrath of your bank. To help catch the cybercriminal and recover its money, your bank lets you bring dodgy charges to its notice. As highlighted in Fraud v Scam: Who Is Liable For Cybercrime, these include:

- Fraud aka Unauthorized Payment: Someone else uses my credit card to make purchases for themselves.

- Scam aka Authorized Payment: I use my credit card to make a purchase. I don’t get the product.

- Deficiency of Service: I use my credit card to make a purchase. I get the product. But it does not work as advertised.

As you can see, grounds for chargeback in a credit card payment go beyond cybercrime. You can raise a dispute not only when you pay the wrong beneficiary by mistake but even when you pay the right beneficiary intentionally.

When you do that, some credit card issuers (e.g American Express) will immediately reverse your charge, no questions asked.

This is a standard feature of credit cards. Amex is able to tout it as a USP b/c banks have kept it under wraps in India. pic.twitter.com/RxEFAoU81j

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) March 23, 2017

Some issuers might ask you a few questions before fulfilling your reversal request. Some others might carry out investigations in the background after hearing you out and accede to your request provided they don’t find any evidence that you’re lying outright. Even if some banks make you run around from pillar to post, eventually, most credit card issuers reverse disputed charges on credit card as long as the dispute has some merit. Because of this, a credit card is called Revocable and Repudiable method of payment (MOP).

When your bank reverses your charge, it pulls the money out from the merchant’s account unilaterally. In other words, the bank does not seek the merchant’s permission to fulfill your chargeback request.

No doubt this leaves credit card highly susceptible to “first party fraud”, where the real owner actually uses the credit card but turns around and claims that somebody else used it. But it’s possible for credit card issuers to use readily available tools to control the amount of first party fraud and ensure that it’s a small irritant compared to the larger goal of reducing cash usage. Besides, as I noted earlier, credit card is a privilege: If a bank finds too much first party fraud on an account, it can just cancel the credit card. The cardholder has no recourse.

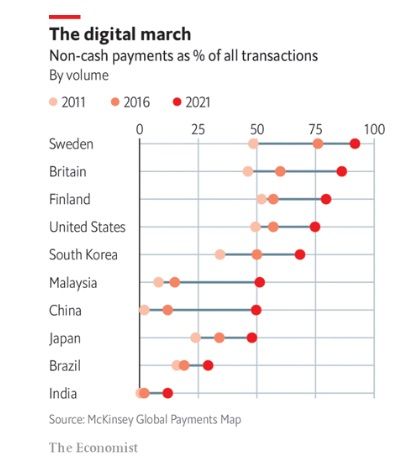

Credit card pioneers designed the product in this manner so as to make it as convenient to use as cash. It worked. Countries like USA, UK, Japan, Australia, and South Korea have achieved a very high usage of credit cards, thus replacing cash to a great extent, as you can see from the following exhibit (Source: McKinsey).

@s_ketharaman: Even 15 years ago, people in USA used credit card for everything and there was virtually zero use of cash for shopping. Unlike people in India who didn’t qualify for credit card and had to wait for an A2A MOP like UPI to go cashless.

As is evident from the above, the basic design of a credit card leans towards protecting the customer’s interest ahead of the merchant’s interest. That’s totally intentional. As an aside, that’s also how PayPal works (“Buyer Protection” versus “Merchant Freeze”).

Now, if you’re a merchant, you might find it unfair that your bank pulls out your money for no fault of yours. You might be peeved at the lack of finality of your receipts. Next only to MDR, chargeback has been the biggest bone of contention between merchants and banks in the 60 year history of credit card.

But credit card has become very popular in advanced markets. Merchants know they’d go out of business if they don’t accept credit card, so they “grin and bear” chargebacks.

@GTM360: When all is said and done, there are only two reasons for a merchant to accept credit card: (1) He will lose business if he does not (2) He will be able to make the customer overspend if he does.

Over time, in order to placate merchants, banks and fintechs launched A2A RTPs like FPS (UK), Venmo, Zelle and eChek (USA). In emerging markets like India, not many people were creditworthy enough to get a credit card, so UPI was launched to ramp up retail payment volumes.

Because the payments industry wanted to assuage merchants’ concerns surrounding credit card chargeback, it designed A2A RTP to be irrevocable and nonrepudiable i.e. exactly the opposite of credit card. Which means that, once he got paid, the merchant kept his money. Because of this feature, merchants love A2A RTPs.

OTOH, as a payor, if you made a payment with UPI, your money is gone forever – whether you made it rightly, wrongly, got a good product or bad product.

As you can see, A2A RTP is biased towards protecting the merchant’s interest. Unlike credit card, nobody could take away the money received by the merchant via an A2A RTP because, by design, the MOP is irrevocable.

Because of the same irrevocability feature, if you pay someone with UPI, your bank cannot reverse the payment. Period. It does not matter whether you paid the right guy or wrong guy. Finders keepers, losers weepers.

In fact, your bank and law enforcement may not have the locus standi to contact the payee and ask him or her to give your money back. Just that, in status-driven cultures, they will not admit this openly. Instead, they will use some smokescreen or the other to hide their helplessness.

Despite all the KYC song & dance required to get a new mobile connection aka SIM, UPI fraudsters can't be tracked because fake documents are apparently used to get a SIM. What's the point in all that friction if it doesn't lead to more security? #UPIFraud pic.twitter.com/wDAr9BUwlP

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) January 13, 2020

It’s really up to you as the payor to contact the payee and request him or her to return your money. Obviously, cybercriminals will tell you to take a walk. That’s assuming that they even answer your call.

Being a basic design feature, irrevocability of UPI cannot be changed so easily.

Besides, even if the technical hurdles are overcome, why would merchants adopt an A2A RTP if it subjects them to the same chargeback tyranny as credit card without delivering the overspending benefit that credit card does?

Quora Link: https://qr.ae/TWY1II.

UPDATE DATED 18 MARCH 2024:

There have been a few updates in the two years since the above original post was published:

1. Regulators in USA are coercing banks to reimburse banks for Zelle scam victims. In response, Zelle is planning to make its A2A payments revocable. Ergo, neither payor nor payee banks will be out of pocket if they reverse a scammy payment.

2. Regulators in UK are imposing 50:50 liability on payor and payee banks for scammy payments. In response, banks will be allowed to hold payments for four working days to investigate them. I called this last year.

Banks will thank regulators for providing the chance to delay payments and earn float income under the pretense that they're "carrying out extra due diligence on the authenticity of the payment".#APP #Scam #A2ARTP https://t.co/QqjN9cDPdA via @theregister

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) September 21, 2023

Alas, FPS will no longer be real time payments. Let alone faster payments, FPS will be one day slower than BACS (which, contrary to doomsday predictions about its future on the eve of FPS go live in May 2008, is still alive and kicking.)

3. There’s no regulatory action yet in India for UPI scam victims.