Both FMCG (Fast Moving Consumer Goods) and DTC (Direct to Consumer) companies manufacture their own products. (NOTE: In some markets, FMCG is called CPG or Consumer Packaged Goods. Source: McKinsey.)

Both of them sell online and via brick-and-mortar stores.

Their products are used by a Consumer i.e. private individual in his or her personal capacity and not by an employee of a company. Ergo both of them belong to the B2C (Business to Consumer) category.

B2C = FMCG + D2C.

Even if they outsource the manufacturing to contract manufacturers, both FMCG and DTC are “product initiators”, as long as the product carries their brand name.

There end the similarities.

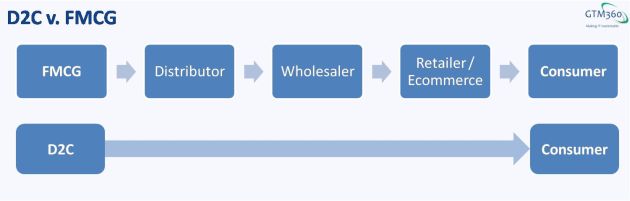

A Fast Moving Consumer Goods company sells its product via distribution channel comprising Distributor, Wholesaler and Retailer i.e. indirectly to the Consumer.

A Direct to Consumer company bypasses the distribution channel and sells its product directly to the Consumer.

As a result, FMCG and D2C have different business models.

As the above exhibit makes it evident, FMCG relies on the traditional distribution channel (aka “trade”) whereas DTC disintermediates the trade.

The canonical examples of D2C brands are Away (luggage), Bonobos (apparel), Casper (mattress), Dollar Shave Club (shaving razors), and Warby Parker (eyewear). (There’s a reason why you don’t see a single Indian brand in this list – more on that in a bit.)

There are literally thousands of FMCG companies in India and the world. Many of them are household names e.g. Amul, Parle, Proctor & Gamble, Unilever.

D2C postures to disrupt the traditional distribution channel.

D2C sells its product directly to the customer … and avoids any middlemen (such as third-party retailers and distribution partners).

By selling to the consumer directly, D2C can avoid retail markups and use these savings to increase quality, service and lower the price. Cutting out the middleman gives D2C companies a chance to create more value for the end client.

By doing so, D2C promises to divert value to a new category, namely, itself.

As we saw in The Six Secrets To Attract Venture Capital, VCs love markets with large and well established demand as against uncertain ones that need to be created anew. Also, as in the case of Fintechs and many other industries, the disruption mantra of DTC resonates strongly with investors. Therefore there’s tons of capital available for D2C, and D2C is very hot in the startup world right now.

Not surprisingly, everyone wants to call themselves DTC.

Including FMCG companies masquerading as DTC.

D2C Bubble

Every new brand being launched is being touted as D2C (even though direct to consumer business is in single digits.)

HUL should reposition itself as a D2C company…it’s stock price would double.

— Rajesh Sawhney (@rajeshsawhney) June 24, 2021

Pureplay DTC startups risk getting torpedoed by such FMCG companies.

In this post, we’ll unpack the D2C business model so that true blue D2C startups can fend off threats from faux D2Cs.

True D2C

As we noted earlier, FMCG sells to the trade whereas DTC sells to the Consumer. This leads to important differences between FMCG and DTC in three areas:

Packing size. FMCG ships in container, truckload, pallet or carton whereas DTC ships single units.

Packing size. FMCG ships in container, truckload, pallet or carton whereas DTC ships single units.

Title. In FMCG, the title of goods is transferred from the FMCG company to Distributor to Wholesaler to Retailer and finally, to the Consumer. In DTC, the title is transferred directly from the DTC company to the Consumer. (A DTC that uses a third-party courier company to ship the goods to its consumers is still a DTC since it retains the title.)

RevRec. As soon as an FMCG company ships its product to the Distributor, it completes the sale and can book the revenue. Back in the day, FMCG companies didn’t bother about what happened to their product once it left their warehouse. With rising competition, some of them do track secondary sales from distributor to wholesaler and tertiary sales from wholesaler to consumer. Nonetheless, these are for marketing purposes. From a pure accounting standpoint, whether the product flies off the retailer’s shelves or lies unsold there, the FMCG company can recognize revenues the moment it raises the invoice on the distributor. See Whose Customer Am I? for more. Obviously, D2C can’t do that.

FMCG masquerading as DTC

During the pandemic, some FMCG companies started selling their products directly to the Consumer, both online and via telephone e.g. Bisleri.

During the pandemic, some FMCG companies started selling their products directly to the Consumer, both online and via telephone e.g. Bisleri.

Bisleri starts direct home delivery for water cans nationally as stores are shut down.

It has become fashionable for these companies to call themselves D2C. This is misleading because they still sell the vast majority of their goods via the traditional distribution channel. Adding D2C as one more channel does not make them a D2C company.

One leading FMCG company recently advertised online sales of its product but the eStore was owned by its distributor. It’s most certainly not a DTC.

Scanned "Buy Now" QR on half-page ad of FMCG co & landed on its online shopping website & thought this is one more FMCG co that has gone DTC during the pandemic.

But, heck no, the website is owned & operated by its distributor!https://t.co/B2HJslYi2Y pic.twitter.com/b6WBb9yvt6— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) June 17, 2021

The business media is guilty of stoking the masquerade. Take Economic Times for example: In its article titled D2C Brands on Funding High Since ’20, India’s largest business daily defines D2C thusly:

D2C brands refer to businesses that have the majority of their revenues or customer acquisition from direct to consumer online channels or started with online first distribution before going omnichannel.

This definition is wrong in more ways than one.

Firstly, the “D2C = online D2C channel” framing is wrong: Online channel already has a name: It’s called online. It shouldn’t be conflated with D2C, which can – and does – operate via brick-and-mortar stores. As D2C forerunner Warby Parker stands testimony, online does not mean DTC. According to Warby Parker and EssilorLuxottica: Irresistible Force, Immovable Object by Byrne Hobart, the eyewear D2C generates 65% of its sales from its physical stores.

Secondly, the definition confuses omnichannel with multichannel. Multichannel is multiple channels operating independently. Omnichannel is when the purchase journey is split across multiple channels. See From Multichannel To Omnichannel & Beyond for more on the difference between multichannel and omnichannel. D2C has only one leg in its distribution, so it can’t be omnichannel. On the other hand, FMCG has 3-4 legs in its distribution, so it has a better chance of being omnichannel.

Why bother?

Terminology matters.

As we’ve seen earlier, D2C and FMCG have different business models. The differences shape existential matters like valuation and availability of venture capital.

Savvy people appreciate why D2C is hot while FMCG and ecommerce are not; whereas randos make a fool of themselves in public by not getting the difference between these two categories.

Where's the problem?

DTC is totally different from Ecommerce.

That said, only people who treat definitions with rigor will get the difference.— GTM360 (@GTM360) August 17, 2021

While on the topic, the term “ecommerce” originated in online sales by retailers. It’s now used more broadly to denote online sales by anybody but, unless otherwise specified, an ecommerce company is a retailer, not DTC.

D2C in India

There’s a lot of action happening in the Indian product and retail spaces. The following companies illustrate the key trends in the two realms:

- iD Idli Dosa Batter. This is a branded product in a market that hitherto had only unbranded products.

- Hash Cigarette. It calls itself a Millennial DTC Cigarette brand and then claims to “empower small retailers and paanwalas through mobile-first tech products.”

- Switz. Many new-age companies begin life as a pureplay DTC company, sell from their own websites and ship directly to consumers. They save on commissions by bypassing the traditional distribution channel. However, over time, they realize that whatever they save by eliminating the middleman is eaten up in rapidly escalating costs of digital advertising (if not feet on street salesforce, in addition). As Divante points out, “the biggest problem for DTC companies is… the new middleman. It is no longer a shopping mall, but Facebook, Instagram, Amazon, and Google; and their services becoming more and more expensive.” To overcome the high CAC inherent in the DTC business model, many of these companies pivot to becoming a seller on Amazon. In both of its operating models – inventory-led and online marketplace – Amazon takes the order, knows the consumer’s identity, cultivates an ongoing relationship with the consumer, and collects valuable data, so it’s a material intermediary aka retailer.

All these companies sell via retailers, so they’re FMCG.

In addition, the third type of company risks becoming a non-company – aka dying – as its segues from DTC to FMCG. It may not have heard the rumors but Amazon allegedly uses the data it collects from sellers on its platform to launch its own private label brands that compete directly with them.

But, because it’s fashionable, many of these Indian companies claim to be DTC.

If you say so.??

— Gotama Gowda (@GotamaGowda) April 17, 2021

This causes confusion. To avoid spreading it, I refrained from naming any Indian D2Cs in the beginning of this post.

That could change soon.

I was recently invited to make a keynote address at a Top D2C Brands event. The email from the event organizer displayed the following logos.

TBH, I’m not familiar with a single brand on this panel but I’ll take the word of the organizer that they’re the leading D2C brands in India.

I’ll have the opportunity to interact with some of these companies during the event and learn more about their business model. If I find a canonical example of a D2C among them, I’ll come back and update this post.

At the start of this post, I mentioned that D2C must be B2C. If I’m allowed to play footloose with that statement, I can’t help noting that Direct to Customer is the default business model in the B2B technology business. Apart from the SAPs, Oracles and Salesforces that can attract Value Added Resellers to distribute their products against commission, most B2B technology vendors have no choice but to hire a salesforce to sell directly to customers and incur the salary costs therein.