In a recent editorial titled “How To Reduce Card Interchange Charges”, Economic Times advocates a combination of subsidy and competition to reduce merchant fees for accepting card payments.

In case you missed it, the government of India has been aggressively pushing cashless payments recently after it demonetized the INR 500 and 1000 notes (and announced plans to introduce newly designed notes in INR 500, 1000 and 2000 denominations).

Since payment card is the most widely used method of cashless payment in India, there’s a renewed focus on stimulating the use of debit and credit cards.

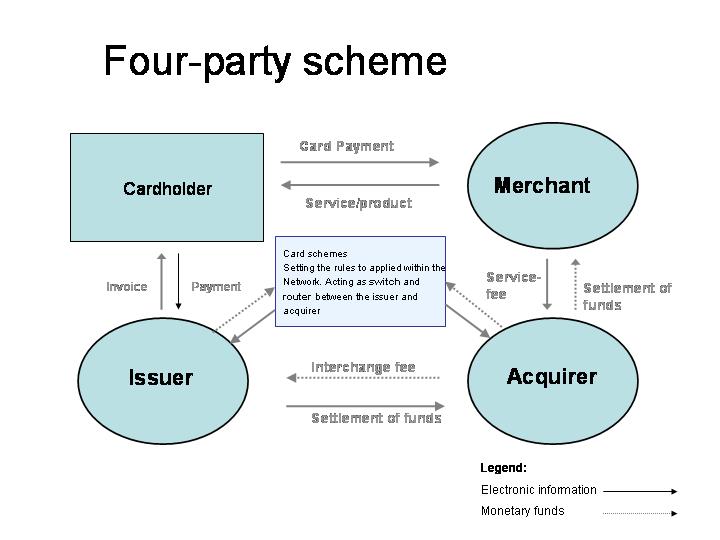

Not surprisingly, Merchant Discount Rate has quickly entered the policymaker’s crosshairs. For the uninitiated, MDR is the “rate charged to a merchant by a bank for providing debit and credit card services.” (Source: Investopedia). In other words, it’s the fees incurred by merchants to gain the ability to accept card payments. MDR is determined by factors such as volume, average ticket price, risk and industry.

A merchant must sign up a Merchant Agreement with an Acquiring Bank and agree to the MDR rates prior to being able to accept debit and credit cards as payment.

At the outset, Economic Times’ suggestion of subsidy is novel. It also sounds fair – after all, if banks and government benefit from the move to a cashless regime, they should be willing to pass on some or all of their gains to merchants and card networks.

However, given that banks and government have their own deficits to plug, what’s the guarantee that they won’t appropriate the gains from going cashless for themselves?

Besides, ET bases its advice on an assumption that the average MDR is 2%. This is an incorrect baseline since it applies only to credit cards, of which there are very few in India compared to debit cards. Given that debit MDR has already been capped by India’s central bank cum banking regulator Reserve Bank of India at 1% (Source: RBI), and the fact that debit card outnumbers credit card by a factor of 30X, the effective MDR stipulated in India is much lower than 2%.

As a result, it’s quite likely that the the blended rate computed by using ET’s formula could actually exceed the effective stipulated MDR, thus raising questions on the need for subsidy.

So the subsidy option may be a non-starter in cutting down merchant fees.

But all’s not lost. Enforcement of stipulated MDR in the following forms can be effective in containing merchant fees.

#1. Enforce RuPay Debit MDR

RuPay charges a fixed debit interchange of 60 paise to Issuer Bank and 30 paise to Acquirer Bank in India. Which is quite low. For the uninitiated, RuPay is a (relatively) new card network launched by National Payments Corporation of India, a wholly-owned retail payments subsidiary of RBI, which in turn is wholly-owned by the government of India. UPDATE dated 21-Jan-2017: I just learned that NPCI is owned by a collection of commercial banks including State Bank of India, ICICI Bank, Punjab National Bank, HDFC Bank et al. It is only promoted by RBI, which has no shareholding in it (Source: MediaNama).

As of now, RuPay offers only a debit card that works only within India.

However, as against the fixed fee levied by RuPay, Indian banks – including public sector behemoths like State Bank of India – seem to be charging an ad valorem rate of as high as 2.95% for RuPay transactions.

Will Visa / MasterCard agree to permanently waive debit MDR when SBI has charged 2.95% on RuPay before #CurrencySwitch? pic.twitter.com/nbRG2iBmCk

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) December 8, 2016

There’s scope to lower merchant fees by nudging banks to accept fixed fees for for RuPay card payments.

#2. Enforce Non-RuPay Debit MDR

As noted earlier, RBI has set the MDR for (non RuPay) debit transactions at a maximum rate of 1%. However, I recently learned that banks seem to be charging a much higher rate in actual practice.

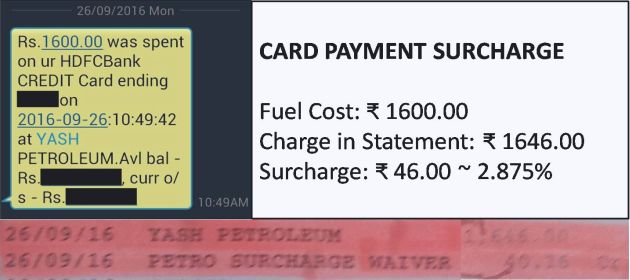

I’ve been using cards to tank up my car for ages. Since times immemorial, I’ve noticed that my card statement displays a higher charge than the amount I pay at the pump. To take an example, I recently filled up fuel worth INR 1600. This matched the figure on the chargeslip I received from the gas station and the realtime SMS alert I got from my card issuing bank immediately after making the payment. However, the same transaction was shown at a higher value of INR 1646.00 in the statement I got a month later. This means the bank has slapped a surcharge of INR 46, which works out to 2.875% on the base figure of INR 1600.

The very next line was PETRO SURCHARGE WAIVER for an amount of INR 40.16. In effect, the bank billed me 2.875% more and refunded almost all of it back in the form of the waiver. The non-refunded amount worked out to INR 5.84 (INR 46 – INR 40.16), which I guess is the non-recoverable government taxes on the surcharge.

Since my cost of choosing a cashless mode of payment is tiny, I’ve never bothered to investigate it. (Considering that 90% of cardholders reportedly never read their statements, I probably am already investigating my statements a bit too much!).

All was well until I heard from my co-workers that their banks slap them a similar surcharge even when they pay for fuel by debit card and, in their case, they don’t get a waiver. In other words, banks charge nearly 3% when RBI has mandated a maximum MDR of 1% for debit card.

Once again, we see that there’s scope to lower merchant fees by compelling banks not to charge more than the stipulated MDR rates for non-RuPay card payments.

Based on my above experiences, I tend to believe that there’s ample opportunity to bring down digital payment costs by enforcing the existing debit MDR rates stipulated by law.

Let me move on to the topic of working out a “fair” MDR rate.

ET recommends using the public sector card network RuPay’s calculations of cost of processing a card transaction as the baseline in arriving at a fair MDR rate.

Going by experience, forget international companies like Visa / MasterCard, it’s questionable if even banks in India will accept RuPay’s version of the cost. They have different software, infrastructure and uptimes, not to mention bonuses for their honchos! In fact, it’s questionable whether these corporations will even agree to the cost-plus method of pricing their services implied by ET.

Now, let’s assume government doesn’t bother with all the niceties and just issues a diktat to slash interchange rates.

Before someone points out that governmental interventions go against the principles of free market, let me point out that banking is a regulated industry in India and everywhere else in the world. Government does have a right to intervene and has done so even in free market pantheons to set MDR rates (although that happened after lengthy public consultations in those countries, but that’s a story for another day).

- EU capped credit interchange at 0.3% (Source: Adyen)

- The Durbin Amendment capped US debit interchange fees at 24 cents per transaction (Source: Bloomberg).

With the basic right of the government to intervene in this market established, let’s see how mandates work in actual practice.

Let me take the example of online payments. Well before the recent remonetization, the Indian government had issued a diktat to state-owned companies to stop levying fees for accepting payments via debit card / credit card / bank transfers. However, at least two PSUs I know continue to levy surcharge for digital payments.

Old news. LIC & MSEB still levy surcharge on credit card payments. Talk is cheap. It's time for action! pic.twitter.com/8CQDOAowaY

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) September 8, 2016

So, once again, we see how better enforcement of existing rules can help bring digital payment costs under control.

Finally, let me turn to driving competition via RuPay, another approach advocated by ET.

For the uninitiated, payment card is a multisided business that bestows incumbents with a huge advantage of “network effect”. While a full treatment of this economic principle is beyond the scope of this blog post, suffice to say that it makes it very difficult to unseat incumbents in this – or any other – business that enjoys network effect.

Not that no one has tried. Card networks like Discover, JCB and MBNA have failed to make a dent on Visa and MasterCard despite trying for decades with equally compelling offerings and multicountry presence.

There’s only one notable exception to this. I’ll come to it in a bit.

Visa and MasterCard are the incumbents in the card network business virtually everywhere in the world including India. RuPay is the new kid on the block. A merely lower MDR rate won’t help RuPay disrupt Visa and MasterCard.

What will?

Maybe following in the footsteps of China UnionPay, which is the only local card network in the world to make a dent on Visa / MasterCard. The Chinese card network offers both debit and credit cards. While it started locally, it quickly took the battle to Visa / MasterCard’s backyard by aggressively expanding overseas.

For RuPay to make a difference, it needs to offer both debit and credit cards and operate internationally. In other words, the Indian government needs to empower NPCI to become a full-service card network with global footprint. Only then will it be able to use RuPay to keep Visa / MasterCard’s MDR in check (though not necessarily low).

India already has in place the regulatory framework and the building blocks of competition required to drive down digital payment costs. What it needs to contain them in actual practice is tighter enforcement of its existing laws and greater empowerment of NPCI to “go ye forth and conquer” the card business globally!