Buyer power in online marketplaces is obvious. Choice of platforms, sales returns, seller rating and venting on social media are among the many ways in which buyer is king in online marketplaces.

Buyer power in online marketplaces is obvious. Choice of platforms, sales returns, seller rating and venting on social media are among the many ways in which buyer is king in online marketplaces.

Platform power is also fairly obvious: Blacklisting errant sellers and withholding payments to them are some of the tools available to the platform to flex its muscle.

I got a whiff of seller power when I heard that Uber’s drivers could rate their passengers. However, I didn’t think much of it since the ratings were not public.

But I got a very tangible experience with seller power when I recently ordered food online.

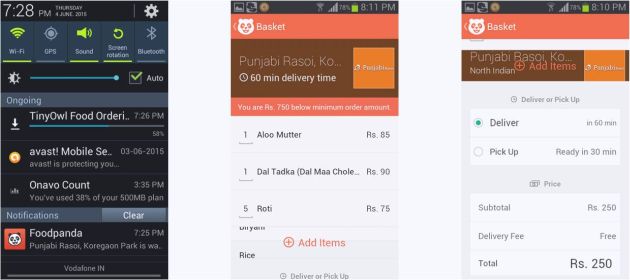

As usual, I fired up my go-to food delivery app FoodPanda and tried to place an order on my favorite restaurant Punjabi Rasoi. In all my previous occasions of ordering for myself, I’ve easily made the restaurant’s minimum order value (INR 150) that qualifies for free home delivery (blame inflation!). However, on this occasion, although I was ordering for my whole family, the app kept flashing an error message saying I was short of the minimum order value by INR 750.

Whoa! Short by 750? How was that possible when the minimum order value has been INR 150 in the past?

I went to the restaurant’s information screen but I couldn’t find any mention of the minimum order value there.

Therefore, I had to infer that it must be INR 1000, being my order total of INR 250 plus the shortfall of INR 750. Despite the inflation blamed above, there was no way I could hit that kind of order value, and I abandoned my order.

I also strongly doubted if this restaurant would’ve really hiked up its minimum order value so sharply, so I called it directly. Its manager accepted my INR 250 order without any demur.

I was wondering what was happening.

I had my answer a half hour later.

Punjabi Rasoi delivered the food. Along with that, I found a whole lot of material – leaflet, tissue, plastic spoon and fork – from TinyOwl.

Founded by fellow alumni from IIT Bombay, TinyOwl is the latest kid on the food delivery app block. Going by all the freebies that came with my food, it appeared that TinyOwl was going all out to attract habitual food delivery app users by poaching its competitors’ restaurants by offering better terms.

This was confirmed when I heard from the industry grapevine that TinyOwl was waiving its customary 15% commission if a competitor’s restaurant switched to its platform. I also noticed that Punjabi Rasoi’s minimum order value on the TinyOwl app was the same old INR 150.

Since search results are displayed by lowest order value first, Punjabi Rasoi got itself banished to the deep recesses of the FoodPanda app by upping its minimum order value to INR 1000. True to the Indian tradition of not saying no to the face, the restaurant had used this trick to shift its allegiance to TinyOwl without actually delisting itself from FoodPanda.

I thought that was a subtle way of exercising seller power.

Interestingly, I got a PUSH notification from FoodPanda saying it was waiting to confirm my order from Punjabi Rasoi. While I appreciated its attempt at abandoner remarketing – a digital marketing best practice that’s still not common in India – there was no way I could go back to FoodPanda under the circumstances.

I’m sure FoodPanda will blame some technical glitch if and when it replies to my tweet. Well, when you’re in the business of using technology to mediate everyday activities, you can’t shirk responsibility for technical glitches.

But I digress.

The point is that sellers can exercise power in online marketplaces and in ways that buyers can notice.

Let me hasten to add that empowering a seller does not mean depriving the buyer. Online marketplaces can simultaneously empower both parties to their mutual benefit.

I found a great example of this in this Quora thread which describes an incident where an Amazon seller talked to a buyer to assuage the latter’s concern about an order and thereby prevent the buyer from canceling the order. In the process, both parties were happy. This was possible only because Amazon permits sellers to interact directly with buyers. (Unlike competitor Flipkart, which I understand does not allow direct communications between buyers and sellers and thus triggers avoidable returns and customer dissatisfaction.)

By empowering its sellers and buyers in this manner, Amazon achieves two desireable outcomes: lower returns and superior customer experience.

So can other online marketplaces. Power equation is not a zero-sum game.