India’s leading online fashion brand Myntra recently shut down its desktop and mobile websites and decided to go mobile app only.

India’s leading online fashion brand Myntra recently shut down its desktop and mobile websites and decided to go mobile app only.

As far as I know, this is an unprecedented move by any ecommerce player anywhere in the world and flies in the face of moves by brands to increasingly hop on to the omnichannel bandwagon.

Customers and pundits have panned the company for taking this decision.

The CEO of Snapdeal, the chief rival of Myntra’s parent company Flipkart, has called it the “most consumer-unfriendly idea I have ever heard of”. Despite all that, Myntra has stuck to its decision. And that too with a fervor that resembles a religious belief more than a business decision. Hence I’m calling it “Myntra’s App Mantra” (MAM).

This post is a teardown of Myntra’s App Mantra. I wish I could claim that my dissembling is the result of extensive research, incisive analysis and a dose of investigative journalism. Instead, I’ll have to admit that it’s merely an attempt on my part to connect a few random dots, based on personal experience and anecdotal evidence.

Personally, I prefer mobile app to desktop web or telephone when I’m ordering a “dedicated” product like a cab.

But, when it comes to “open” categories like apparels and gadgets, I prefer brick-and-mortar stores or desktop web.

Since Myntra belongs to the latter category, MAM is repugnant to my shopping behavior.

However, I’m likely to be in the minority since I have a choice between desktop web and mobile app. That’s not the case for hundreds of millions of Indians for whom mobile is the first and only gateway to online commerce. Going by that, MAM is not all that harebrained.

Besides, MAM lets Myntra do a lot of things that are not possible on its desktop website:

- Collect insight from all users, not just the ones who are logged in, because a mobile app is a “walled garden” in which nobody is anonymous

- Track consumer’s location using a smartphone’s LBS features

- Send targeted offers to the user’s smartphone. These offers can be personalized for a “segment of one” if Myntra so wishes. Such a granular level of targeting is not possible on any other media – print, TV or web

- Disintermediate Google Ads and Affiliate Partners by connecting directly with existing customers, thereby saving advertising and affiliate margin costs

- Make it hard for users to do comparison shopping – which is de rigueur on desktop web and a major cause of shopping cart abandonment on the traditional online platform.

In short, Myntra’s App Mantra helps Myntra to increase conversion and decrease SG&A costs. Which is a great thing for the company.

But not necessarily for its customers for one or more of the following reasons:

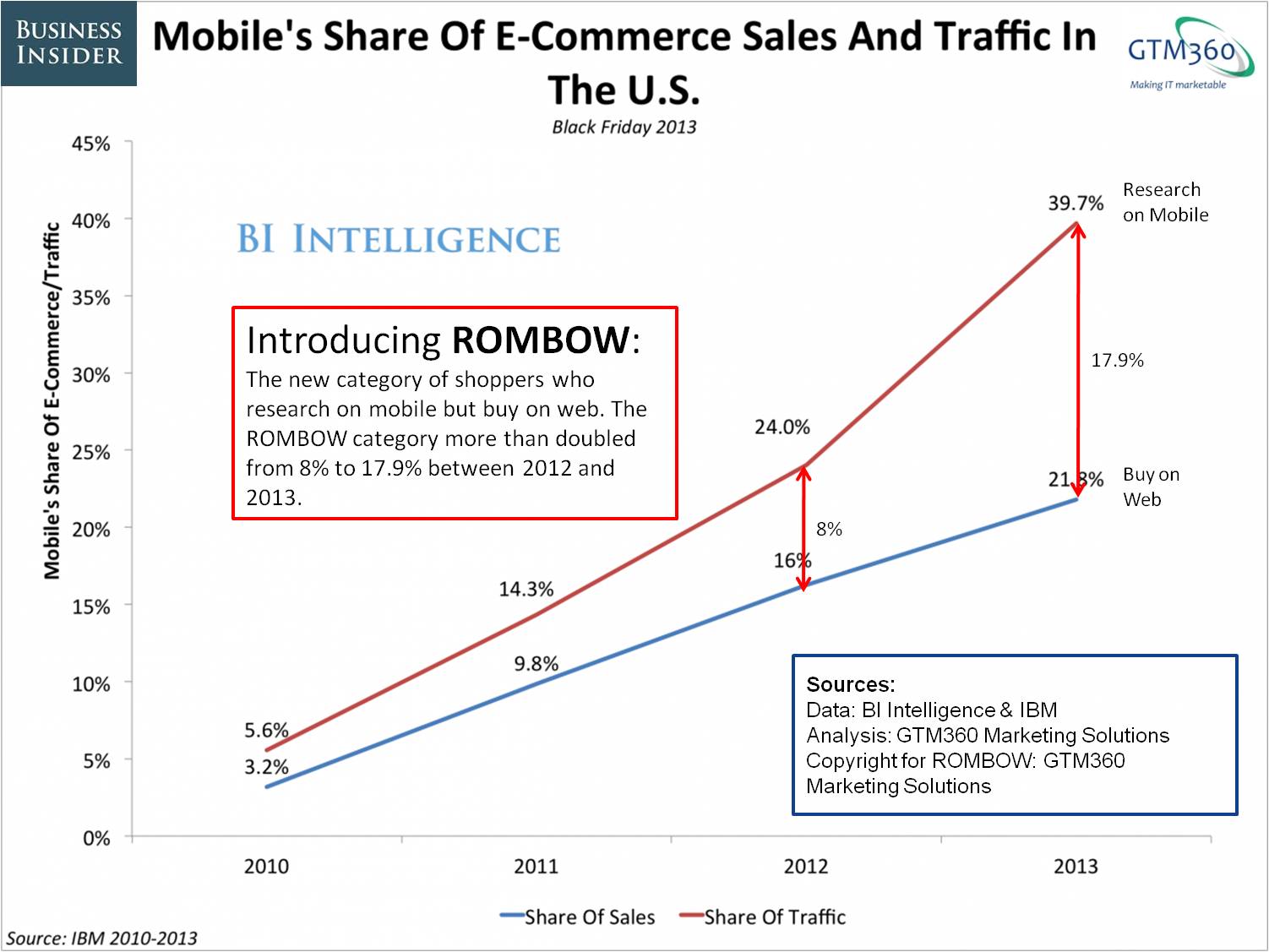

- Many people are not comfortable shopping for apparels, bags and other fashion items on the small screen of a smartphone. According to New York Times, “Despite spending close to three hours of each day staring at their mobile phones, Americans continue to do the vast majority of their online shopping through desktop and laptop computers”. We call this shopping behavior ROMBOW or “Research On Mobile Buy On Web”. According to Business Insider data and our analysis, the ROMBOW segment doubled last year. But these figures are for US consumers. We don’t know whether they reflect Indian shopping behavior. Interestingly, not just Myntra but many other ecommerce companies have been claiming exactly the opposite behavior for consumers in India.

- People keep running out of memory in their smartphones and they need to delete some apps from time to time. An infrequently used ecommerce app like Myntra is likely to face the ax to make space for cab, food delivery, grocery and other more frequently used apps. (While a company executive recently claimed that a Myntra customer uses the app eight times a month, that seems like wishful thinking and I’m ignoring this metric.)

- Some people just don’t want their suppliers to track them so closely. But that segment must be tiny since, while justifying the move to “app-only” regime, not just Myntra but many other companies have brazenly touted their new-found ability to track location and spends via mobile apps without even appearing to pay lip service to consumer privacy preferences.

Myntra has tried to offset these issues by introducing personalization, deep-linking and “authentically mobile” features in the latest version of its app. However, they haven’t solved my fundamental problem: I couldn’t decide whether a leather bag costing a bomb was right for me even on Myntra’s website; obviously, I’m not going to manage that feat on a smartphone screen; when my smartphone ran out of space, some apps had to go, and Myntra was one of them.

So, I bid farewell to Myntra. Going by the rants on the blogosphere, I’m not alone.

Therefore, MAM is bound to cause some loss of customers.

As long as the “some” in the aforementioned sentence is within reasonable limits, that’s not such a bad thing.

According to common wisdom, revenues can grow only by acquiring more customers. That’s true but only until a company achieves critical mass. Beyond that point, a company can grow revenues even by shedding customers if it can increase its share of remaining customers’s wallets. With “10M – 50M” installs of just its Android app, Myntra might have reached critical mass and it might just be possible for the company to take its revenues to the next level by engaging deeper with its existing customers, increasing their purchase frequency and growing their ticket size.

This approach is not unique to ecommerce: Other industries have done this for ages e.g.

- Banks have cut down rural clientele, shed low balance accounts and pruned their customer base in many other ways, as highlighted here and here, yet they’ve become bigger and more profitable over the years.

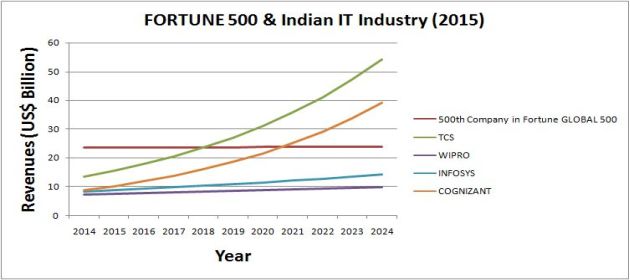

- A leading IT services company learned that the bottom 30% of its customer base was sapping its management resources. It took a conscious decision to shed this segment and divert its attention to the Top 40% of its customer base that was not only profitable but offered immense growth potential. The company’s 10X growth over the next decade is proof that this strategy works.

If customer attrition can work for banks and IT companies, it can equally well work for Myntra.

Besides, it offers an additional benefit to Myntra. As widely reported, every customer is a loss center for many Consumer Internet companies including Myntra. In other words, more customers means more loss. Culling some customers is a good way for Myntra to reduce losses and slowly inch its way up to profitability (apart from reducing discounts and taking other steps that may or may not be practical in a crowded market.) This resonates well with Myntra’s stated goal of turning profitable by FYE 2016.

Only time will tell how Myntra’s App Mantra will play out but I’m convinced that it’s not half as dumb as it’s made out to be.